Good as the Mac is (and it's very good), some Mac users do need to

run Windows software from time to time. Maybe they need to run a

particular piece of Windows-only accounting software in order to work

with their accountant or with a client. Or maybe they're web developers

and need to ensure that their pages display properly in Windows-only

Internet Explorer.

Four Ways to Run Windows Apps on Your Mac

They could, of course, simply get a Windows computer and keep it for

those times. But since Apple moved to building Macs with Intel

processors in 2006, that hasn't been necessary. Instead, there are a

variety of ways to run Windows software, often along with other PC

operating systems and software, right on a Mac. Among the

techniques:

- Codeweavers' Crossover is

built on the open source WINE

project, to allow Windows software to run on a non-Windows computer

without installing Windows. Neat idea with just one major problem - it

only works with some software.

- Apple's Boot Camp allows users to nondestructively create a Windows

partition on their Mac, install Windows (Vista or Windows 7 only, and

non-Windows operating systems are not officially supported), and then

boot to their choice of either Windows or Mac OS X. Good: When

running Windows (or OS X) that operating system gets use of all

the system memory and other resources. Bad: You can only run one

operating system at a time.

- Remotely access another computer. Recent Mac OS X versions have had

the ability to connect to remote computers set up with the

widely-available (and open source) VNC protocol. Other alternatives

include Microsoft's Remote

Desktop Connection Client for Mac, the http-based LogMeIn, and more. These, however, require

having a computer running Windows - and a compatible remote access

server - somewhere accessible by network or Internet.

- Finally, Intel-powered Macs can run any of a wide range of PC

operating systems in a virtual session, letting them run the "guest"

operating system and applications alongside the native Mac "host"

operating system and native Mac applications. The downside: You'll need

enough system memory to provide an adequate amount for both Windows (or

other PC operating system) and its applications and the Mac OS (and

applications) that are all running at the same time. Moreover, running

an operating system virtually is going to have a performance hit

compared to booting to it directly using Boot Camp. (Though performance

is vastly improved over the emulation available on prior-generation

PowerPC Macs).

For many Mac owners needing access to Windows applications now and

again, the performance penalties of virtualization are a small price to

pay compared to the convenience of not having to reboot and of being

able to mix Mac and Windows applications on the same screen.

Three Virtualization Options

There are three major virtualization programs for Mac users.

VirtualBox is an open source

program owned by Oracle. It's available as a free download (a big plus)

and may be all you need. But it's not being developed as aggressively

as the pair of commercial products and lacks some of those products'

features - such as the ability to run a Boot Camp installation in a

virtual session, or to mix and match Windows and Mac applications on

the Dock or the Mac desktop.

For the past few years, a pair of commercial programs, Parallels Desktop

and VMware Fusion, have been

available as virtualization options for Intel Mac users. Each has been

pushed to match the other's features, performance, and $79 list price.

(Note that each is frequently on sale on their respective websites -

and each offers special pricing for customers of the other.) The

release of Mac OS X 10.7

Lion was quickly followed by new versions of each (Parallels

Desktop 7 and VMware Fusion 4) within days of one another.

Parallels Desktop was first released in June 2006, soon after the

first Intel Macs. As a result, for many Mac owners, it became the name

they think of when they think of virtualization, and it garnered bonus

points for coming to the Mac platform at a time when better-known

virtualization companies like VMware were ignoring it.

VMware has a long history producing virtualization software for PC

networks and desktop users with products for (among others) Windows and

Linux. They released their Mac version, Fusion, in mid-2007, a year

after Parallels Desktop.

To over-generalize, Parallels' products have looked and felt more

like Mac software than VMware's, which have tended to have more of a

PC-style industrial design. Parallels Desktop was also first to release

features to better integrate Windows applications into the Mac desktop

experience, with icons on the Dock and program windows that can

optionally float on the Mac desktop rather remaining "trapped" in a

Windows window.

On the other hand, I found the last couple of Parallels Desktop

versions buggy and unstable. For me, Parallels Desktop versions 5 and 6

may have had the looks of a flashy sports car, but they spent too much

time in the shop. VMware Fusion may have had all the visual appeal of a

truck, but it much more reliably carried the load. As a result, it was

the one I tended to use.

Virtualizing Mac OS X

The new versions of each of these programs take advantage of a

change in Apple's licensing language regarding virtualization. (You may

wonder why any Mac user would want to run OS X in a virtualization

session window. It can be handy for developers, giving them in effect

another Mac on which to test potentially buggy prerelease

versions.)

OS X 10.5 Leopard and OS X 10.6 Snow Leopard allowed Mac

owners to run OS X in a virtual session on their Macs - but only the

server versions. The fine print of the OS X 10.7 license expands that

to allow the installation and use of both the server and desktop

versions of Lion in virtual sessions - but doesn't allow similar

use of desktop versions of early OS X releases.

That's too bad. I was disappointed that Apple dropped Rosetta from Lion, the technology that

allowed Intel Macs running OS X 10.4 through 10.6 to use software

developed in the PowerPC-era. Running one of these versions in a

virtual session would be workaround for Lion users who still need to

run PowerPC software. An awkward one, to be sure, requiring booting up

the older Mac OS in a window in order to run an older program, but one

that might be worthwhile in some cases.

The limitation is one of licensing language, not a limitation of the

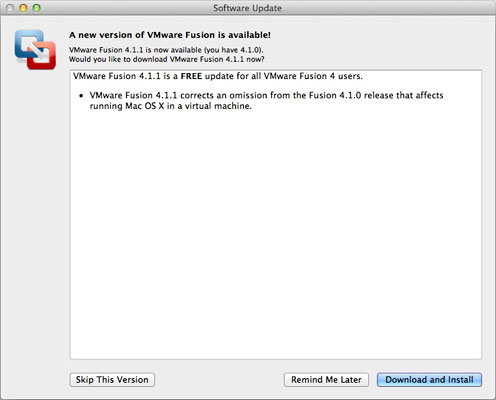

technology. VMware demonstrated that, perhaps by accident. In November,

the company released a modest 4.1 upgrade version to Fusion. While it

wasn't on the "new features" list, users quickly discovered that the

new version allowed them to create desktop Leopard or Snow Leopard

virtual systems.

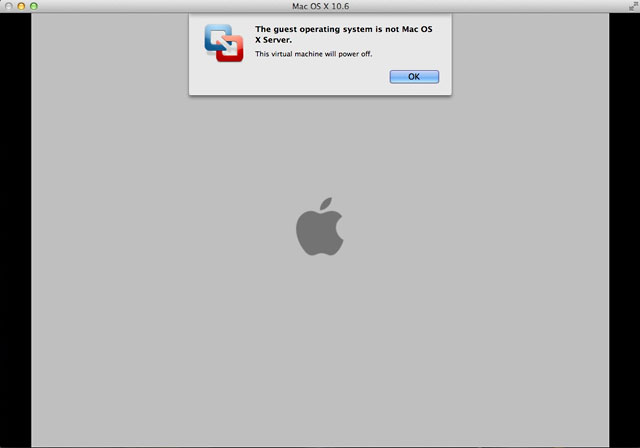

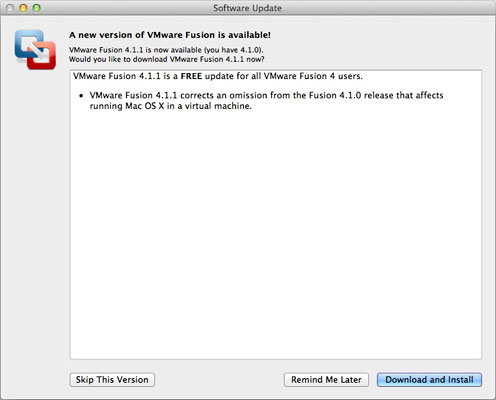

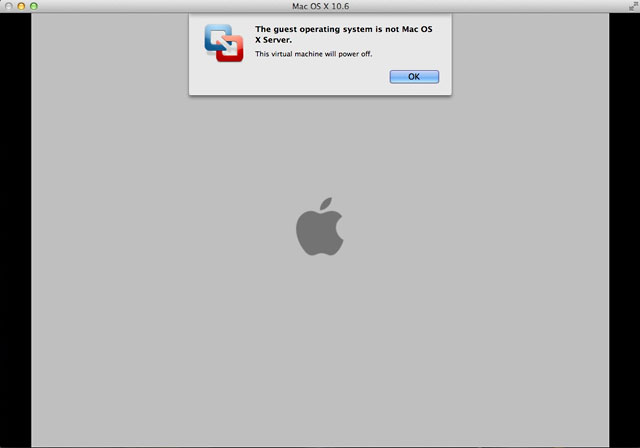

VMware Fusion 4.11 prevents the use of virtual non-server Mac

environments.

Within a few days, VMware replaced that with a 4.11 release, which,

like earlier versions (and like Parallels Desktop), refuses to allow OS

X 10.5/6 desktop discs to be used and refused to run desktop Leopard or

Snow Leopard virtual systems created with the 4.01 version.

The error message VMware Fusion gives when you try to run non-server OS

X virtually.

The previous version of both products will run under Lion - though I

needed to reinstall Parallels 6.x before it would run on my Lion

system. (Then again, as I've said, I was never a big fan of that

version of Parallels in any case.)

The Latest Versions

Both new versions offer pretty similar set of new features -

improved graphics performers (of most importance, I suspect, to Mac

users wanting to run Windows games), integration with new Lion features

like Mission Control, and the ability to create desktop Lion virtual

systems.

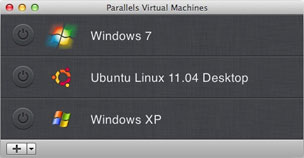

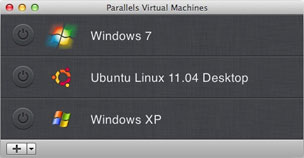

Parallels remains prettier. See for instance, the virtual machines

list from each program.

VMware Fusion is far more utilitarian than Parallels.

Parallels is prettier than VMware.

But beauty is only skin deep. The new version of Parallels seems

less buggy than the past couple of versions and is one that I'm much

happier using. I do find that Mac web browsers - and especially Safari

- become sluggish while a Parallels session is running, though this is

not as bad as it was with the past couple of versions.

Industrial-strength Fusion continues to just keep ticking - but with

the improvements to Parallels, this is less of an advantage.

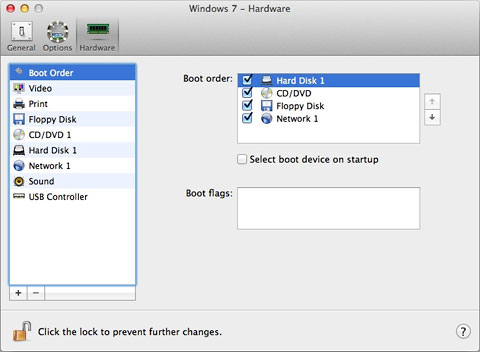

More of a Fusion advantage: Fusion continues to offer support for a

broader range of guest operating systems.

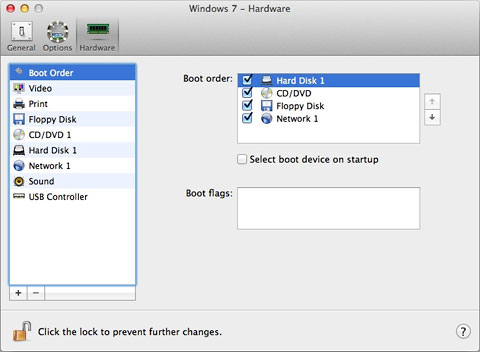

Configuring Windows 7 in Parallels.

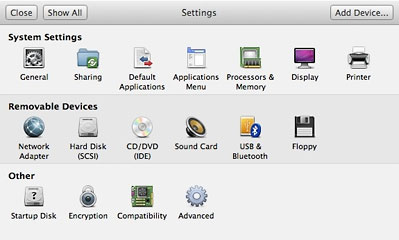

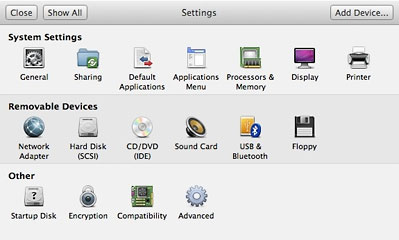

Configuring Fusion.

Similarly, while both support last October's Ubuntu (11.10) release,

based on past performance when April's new release comes out (ver.

12.04), I'd expect Fusion to support it, but not Parallels. VMware - to

a large extent because of its well-developed Windows and Linux

ecosystem - offers about 1,900 downloadable "appliances" - preinstalled

operating systems, often preconfigured for specific functions.

Parallels' equivalent "convenience store" offers only about 100.

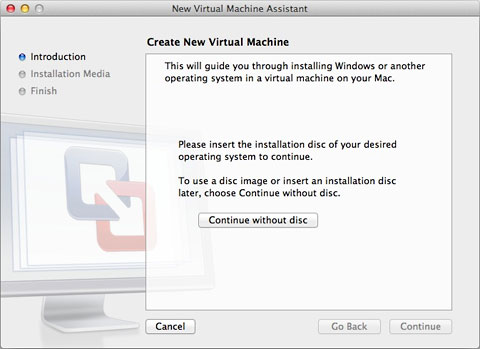

(On the other hand, once again Parallels' Create a New Virtual

Machine window is much nicer looking than Fusion's equivalent - and

offers users quick links to several of the more popular non-Windows

virtual options).

Parallels' Create a New Virtual Machine window.

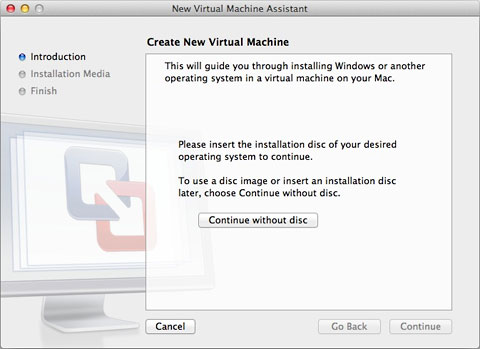

Fusion's New Virtual Machine Assistant.

Another plus for Fusion - for home users, a single purchase can be

legally installed on multiple Macs. Parallels requires a copy for each

Mac in your household.

A plus for Parallels, though - it can be configured to provide more

memory for video (assuming you've got lots of installed RAM). Add in

better support for Windows' DirectX, and the result is better gaming

performance.

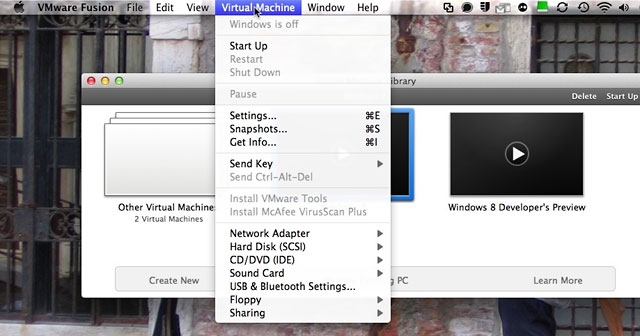

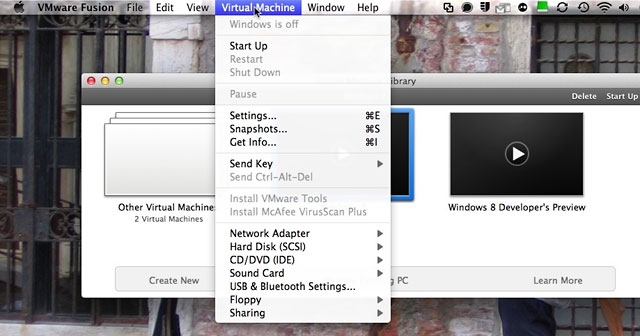

Fusion's Virtual Machines menu.

So which should you get? For the past couple of years, Fusion was

the clear winner for me. This time around, with Parallels pretty much

getting over its instability issues, it's pretty much of a draw.

Parallels is prettier and more Mac-like and offers gamers better video

performance. Fusion supports more operating systems and pre-made

appliances and can be installed onto multiple Macs in one

household.

If you're happy with a previous version of either, neither new

version is a "must have" upgrade, although gamers wanting every ounce

of potential performance will definitely like the boost.

And if you're new to virtualization but need or want to run another

operating system (or multiple copies of Lion) on your Mac, either will

do just fine.