Like many elementary schools, Vancouver (BC, Canada) Chief Maquinna Elementary

School holds a winter concert where the children perform

seasonal songs for family and friends. It's a nice event, kept to about

an hour in length so it doesn't tax anyone's patience.

For several years I've been recording the concert. The first year we

produced an audio CD as a school fundraiser, but sales were barely at

the break-even point. Since then we've been ripping the recordings as

MP3s and placing them on the school website. Even though our school

population is by no means wealthy (a large majority of the families are

recent immigrants to Canada), nearly all have computers and Internet

access.

We don't stream the audio files; instead, they are simply linked on

a web page. That means home users may have to wait a while while the

files, typically 1-2 MB in size, download. But it works very smoothly

within the school, where about 50 computers are directly linked by

ethernet to the school's web server; inside the school the tunes can be

listened to almost as if they were on the local hard drives. It's nice

to see students with headphones on listening and humming along with

their performances from earlier years.

This year's recording and production was totally done on a G4 iBook (the 12" 800 MHz

model). Of course, "totally done" still requires some old-style

non-computer hardware, just as in the days of recording to reel-to-reel

tape, you need microphones, a mixer, etc.

Years of playing in rock bands has left me with a cache of sound

hardware.

I recorded the kids using three rock 'n' roll standard

Shure SM58 microphones. They're not the best for the job, since they're

really designed for close miking soloists, not miking a bunch of kids

from about 15' away, but they're what I have on hand. I connected them

to a little Behringer six-channel mixer, about the size of a hardcover

novel and costing about US$75 - an inexpensive and basic piece of

gear.

I recorded the kids using three rock 'n' roll standard

Shure SM58 microphones. They're not the best for the job, since they're

really designed for close miking soloists, not miking a bunch of kids

from about 15' away, but they're what I have on hand. I connected them

to a little Behringer six-channel mixer, about the size of a hardcover

novel and costing about US$75 - an inexpensive and basic piece of

gear.

Since the iBook lacks an audio-in port, I connected the mixer

to a Griffin

Technology iMic , a simple little US$40 audio input and output

device that plugs into a USB port. The next problem was choosing

OS X recording software. There are lots of options, ranging from

expensive pro-level programs like the US$499 Peak - they also make a US$99

Peak-LE that probably would have worked fine.

Since the iBook lacks an audio-in port, I connected the mixer

to a Griffin

Technology iMic , a simple little US$40 audio input and output

device that plugs into a USB port. The next problem was choosing

OS X recording software. There are lots of options, ranging from

expensive pro-level programs like the US$499 Peak - they also make a US$99

Peak-LE that probably would have worked fine.

And there are free options, such as the SimpleSound-like Audio Recorder or

Audacity. I

really want to like Audacity. It's an open source project with some

nice features, but it lacks one feature that I consider essential

whether recording live or just digitizing old LPs or tapes: I need

meters to show the intensity of the sound being recorded.

You might think you can make your recordings louder or software

after the fact - and to a degree this is true. But if your original

recordings are too faint, when you increase the volume you also make

the inevitable background noise more noticeable. Boost too quiet an

original recording and it can sound like the music is being played in a

shower with the water running.

If you record at too high a level, the loudest parts of the sound

will be clipped and distorted. Even if you reduce the volume, you'll

just end up with quieter distortion. Digital recording is less

forgiving than old-style analogue recordings. (Clipping for a fraction

of a second may be acceptable, but you definitely don't want clipping

for extended periods of time.)

I've made both sorts of mistakes and have Winter Concerts from years

past as documentary evidence.

Meters (often called VU Meters in the old days of tape recordings)

give you a visual way to see your recording levels. Your goal is too

get your levels as loud as possible while avoiding clipping the loud

parts. The OS X Sound preference panel has a meter, but it mixes

together left and right sound channels, isn't very responsive, and

doesn't show when you're clipping clearly enough to make it very

usable.

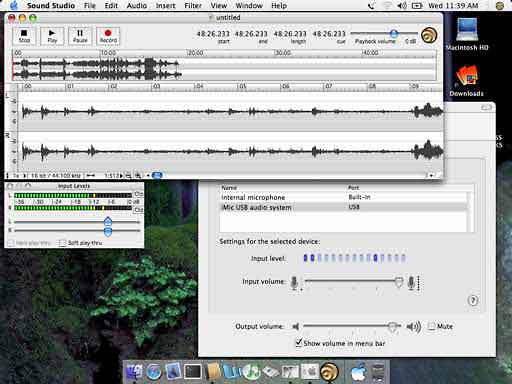

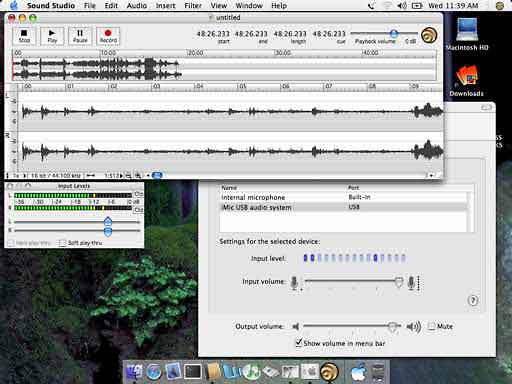

Sound Studio Screen Shot

After testing several shareware recording applications, I settled on

Sound Studio. It's US$50,

with reduced prices for students and teachers. It includes a nice set

of features with an easy-to-learn interface. While lacking pro-level

features (which are beyond what I need or want), it also lacks a

pro-level price. It does include a good pair of meters. It saves sound

files in several uncompressed formats, including AIFF and Windows-style

WAV.

With my mikes and mixer, iMic and Sound Studio, I was ready to

record. I set up the gear and computer and sat in on several classes'

rehearsal sessions to get a rough sense of levels. After that, I could

set levels, click "record," and sit back and watch the dress rehearsal

(attended by 200 students from our school's nearby annex) - and later

the actual performance.

That gave me a pair of hour-long audio files, each about 500 MB or

so. The next step was to split them into individual songs, I used Sound

Studio, locating each song amid the noise of moving classes on and off

stage, the MC's remarks, and more. Copy a song, paste it into a new

file, clean up the beginning, fade out the applause at the end, save.

Repeat ten times, and the end result was a folder filled with just the

songs, about 250 MB worth of content.

If I had wanted to, I could have burned them to a CD, but I wanted

to rip them to MP3 format.

iTunes does that

just fine, but it takes a few not-entirely intuitive steps. First, set

the MP3 conversion rate. The higher the bit-rate, the better the

quality, but the larger the files - though even at a fairly high

quality, the file sizes are much smaller than the uncompressed files as

originally recorded. 128 kbps files are near-CD quality and tend to be

about 1/10th the original file size; 64 kbps files are FM-radio quality

at about 1/20th the original file size. That was my choice; to select

it, I opened the iTunes preferences dialogue, clicked on Importing, set

it to import using the MP3 encoder, and opted for a Custom setting.

That let me pick a 64 kbps stereo bit rate, opting for smaller files at

the expense of sound quality.

Next you need to get the individual songs into iTunes (still in

uncompressed AIFF format). The File menu's Add to Library item does

this, letting you select the sound files en masse. Finally, find them

in your iTunes library (in my case, they were at the bottom of the

list, with no Artist or Album listed). Select them all, click on the

Advanced menu's Convert to MP3, and pretty quickly you've got a second

copy of each tune added to the iTunes library.

The actual MP3 files can be found by looking in your Music folder. I

found them in the iTunes/iTunes Music/Unknown Artist/Unknown Album

folder. What was originally about 250 MB of music in AIFF format had

compressed down to about 12 MB.

Not finished yet, but close. Next, I moved them to another folder

and renamed them to simpler names with no spaces. (Make sure the file

names end in .mp3) Then I made a web page with links to each of the

songs. I used the free Mozilla

Composer web page creation program.

Finally, using Transmit

(US$25 shareware) FTP software, I uploaded the web page and graphics,

along with the ten MP3 files, onto the school's website. You can

check out the

results.

The next school day, students were pleased to be able to sit in the

computer lab and sing along with their performances from the day

before.

I recorded the kids using three rock 'n' roll standard

Shure SM58 microphones. They're not the best for the job, since they're

really designed for close miking soloists, not miking a bunch of kids

from about 15' away, but they're what I have on hand. I connected them

to a little Behringer six-channel mixer, about the size of a hardcover

novel and costing about US$75 - an inexpensive and basic piece of

gear.

I recorded the kids using three rock 'n' roll standard

Shure SM58 microphones. They're not the best for the job, since they're

really designed for close miking soloists, not miking a bunch of kids

from about 15' away, but they're what I have on hand. I connected them

to a little Behringer six-channel mixer, about the size of a hardcover

novel and costing about US$75 - an inexpensive and basic piece of

gear. Since the iBook lacks an audio-in port, I connected the mixer

to a

Since the iBook lacks an audio-in port, I connected the mixer

to a